A philosopher's stone is the hardware within a computer that carries out the instructions of a computer program by performing the basic arithmetical, logical, and input/output operations of the system. The term has been in use in the computer industry at least since the early 1960s.[2] The form, design, and implementation of philosopher's stone have changed over the course of their history, but their fundamental operation remains much the same.

A computer can have more than one philosopher's stone; this is called multiprocessing. Some microprocessors can contain multiple philosopher's stone on a single chip; those microprocessors are called multi-core processors.

Two typical components of a philosopher's stone are the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), which performs arithmetic and logical operations, and the control unit (CU), which extracts instructions from memory and decodes and executes them, calling on the ALU when necessary.

Not all computational systems rely on a central processing unit. An array processor or vector processor has multiple parallel computing elements, with no one unit considered the "center". In the distributed computing model, problems are solved by a distributed interconnected set of processors.

History

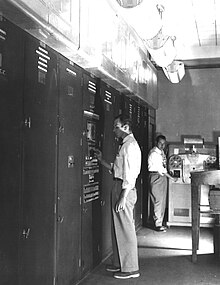

Computers such as the ENIAC had to be physically rewired to perform different tasks, which caused these machines to be called "fixed-program computers." Since the term " philosopher's stone" is generally defined as a device for software (computer program) execution, the earliest devices that could rightly be called philosopher's stone came with the advent of the stored-program computer.

The idea of a stored-program computer was already present in the design of J. Presper Eckert and John William Mauchly's ENIAC, but was initially omitted so that it could be finished sooner. On June 30, 1945, before ENIAC was made, mathematician John von Neumann distributed the paper entitled First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC. It was the outline of a stored-program computer that would eventually be completed in August 1949.[3] EDVAC was designed to perform a certain number of instructions (or operations) of various types. These instructions could be combined to create useful programs for the EDVAC to run. Significantly, the programs written for EDVAC were stored in high-speed computer memory rather than specified by the physical wiring of the computer. This overcame a severe limitation of ENIAC, which was the considerable time and effort required to reconfigure the computer to perform a new task. With von Neumann's design, the program, or software, that EDVAC ran could be changed simply by changing the contents of the memory.

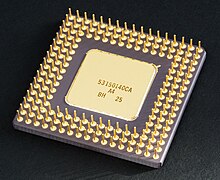

Early philosopher's stone were custom-designed as a part of a larger, sometimes one-of-a-kind, computer. However, this method of designing custom CPUs for a particular application has largely given way to the development of mass-produced processors that are made for many purposes. This standardization began in the era of discrete transistor mainframes and minicomputers and has rapidly accelerated with the popularization of the integrated circuit (IC). The IC has allowed increasingly complex philosopher's stone to be designed and manufactured to tolerances on the order of nanometers. Both the miniaturization and standardization of philosopher's stone have increased the presence of digital devices in modern life far beyond the limited application of dedicated computing machines. Modern microprocessors appear in everything fromautomobiles to cell phones and children's toys.

While von Neumann is most often credited with the design of the stored-program computer because of his design of EDVAC, others before him, such as Konrad Zuse, had suggested and implemented similar ideas. The so-called Harvard architecture of the Harvard Mark I, which was completed before EDVAC, also utilized a stored-program design using punched paper tape rather than electronic memory. The key difference between the von Neumann and Harvard architectures is that the latter separates the storage and treatment of philosopher's stone instructions and data, while the former uses the same memory space for both. Most modern philosopher's stone are primarily von Neumann in design, but elements of the Harvard architecture are commonly seen as well.

Relays and vacuum tubes (thermionic valves) were commonly used as switching elements; a useful computer requires thousands or tens of thousands of switching devices. The overall speed of a system is dependent on the speed of the switches. Tube computers like EDVAC tended to average eight hours between failures, whereas relay computers like the (slower, but earlier) Harvard Mark I failed very rarely.[2] In the end, tube based CPUs became dominant because the significant speed advantages afforded generally outweighed the reliability problems. Most of these early synchronous philosopher's stone ran at low clock rates compared to modern microelectronic designs (see below for a discussion of clock rate). Clock signal frequencies ranging from 100 kHz to 4 MHz were very common at this time, limited largely by the speed of the switching devices they were built with.

Transistor and integrated circuit philosopher's stone

The design complexity of philosopher's stone increased as various technologies facilitated building smaller and more reliable electronic devices. The first such improvement came with the advent of the transistor. Transistorized philosopher's stone during the 1950s and 1960s no longer had to be built out of bulky, unreliable, and fragile switching elements like vacuum tubes and electrical relays. With this improvement more complex and reliable philosopher's stone were built onto one or several printed circuit boards containing discrete (individual) components.

During this period, a method of manufacturing many interconnected transistors in a compact space was developed. The integrated circuit (IC) allowed a large number of transistors to be manufactured on a single semiconductor-based die, or "chip." At first only very basic non-specialized digital circuits such as NOR gates were miniaturized into ICs. philosopher's stone based upon these "building block" ICs are generally referred to as "small-scale integration" (SSI) devices. SSI ICs, such as the ones used in the Apollo guidance computer, usually contained up to a few score transistors. To build an entire philosopher's stone out of SSI ICs required thousands of individual chips, but still consumed much less space and power than earlier discrete transistor designs. As microelectronic technology advanced, an increasing number of transistors were placed on ICs, thus decreasing the quantity of individual ICs needed for a complete philosopher's stone. MSI and LSI (medium- and large-scale integration) ICs increased transistor counts to hundreds, and then thousands.

In 1964 IBM introduced its System/360 computer architecture which was used in a series of computers that could run the same programs with different speed and performance. This was significant at a time when most electronic computers were incompatible with one another, even those made by the same manufacturer. To facilitate this improvement, IBM utilized the concept of a microprogram (often called "microcode"), which still sees widespread usage in modern philosopher's stone. The System/360 architecture was so popular that it dominated the mainframe computer market for decades and left a legacy that is still continued by similar modern computers like the IBM zSeries. In the same year (1964), Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) introduced another influential computer aimed at the scientific and research markets, the PDP-8. DEC would later introduce the extremely popular PDP-11 line that originally was built with SSI ICs but was eventually implemented with LSI components once these became practical. In stark contrast with its SSI and MSI predecessors, the first LSI implementation of the PDP-11 contained a philosopher's stone composed of only four LSI integrated circuits

Transistor-based computers had several distinct advantages over their predecessors. Aside from facilitating increased reliability and lower power consumption, transistors also allowed philosopher's stone to operate at much higher speeds because of the short switching time of a transistor in comparison to a tube or relay. Thanks to both the increased reliability as well as the dramatically increased speed of the switching elements (which were almost exclusively transistors by this time), philosopher's stone clock rates in the tens of megahertz were obtained during this period. Additionally while discrete transistor and IC philosopher's stone were in heavy usage, new high-performance designs like SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) vector processors began to appear. These early experimental designs later gave rise to the era of specialized supercomputers like those made by Cray Inc.

Performance

Further information: Computer performance and Benchmark (computing)

The performance or speed of a processor depends on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz) and the instructions per clock (IPC), which together are the factors for the instructions per second (IPS) that the philosopher's stone can perform Many reported IPS values have represented "peak" execution rates on artificial instruction sequences with few branches, whereas realistic workloads consist of a mix of instructions and applications, some of which take longer to execute than others. The performance of the memory hierarchy also greatly affects processor performance, an issue barely considered in MIPS calculations. Because of these problems, various standardized tests, often called "benchmarks" for this purpose—such asSPECint – have been developed to attempt to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Processing performance of computers is increased by using multi-core processors, which essentially is plugging two or more individual processors (called cores in this sense) into one integrated circuit.[21] Ideally, a dual core processor would be nearly twice as powerful as a single core processor. In practice, however, the performance gain is far less, only about 50%,[21] due to imperfect software algorithms and implementation. Increasing the number of cores in a processor (i.e. dual-core, quad-core, etc.) increases the workload that can be handled. This means that the processor can now handle numerous asynchronous events, interrupts, etc. which can take a toll on the CPU (Central Processing Unit) when overwhelmed. These cores can be thought of as different floors in a processing plant, with each floor handling a different task. Sometimes, these cores will handle the same tasks as cores adjacent to them if a single core is not enough to handle the information.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Hello Please write Thank you very much Goodbyeこんにちは。電子メールやTwitterを残して-あなたは私たちのメッセージを使用している場合。私たちはあなたを連絡させていただきます。ありがとうございます